Just need the Sun & Wind to travel around Mars

U0204912 Lin Zhiqiang

Explore Mars with Robots

There are a number of limitations and factors that are affecting exploration in distant planets and stars like Mars. One of them is battery life. NASA scientists are always looking for sustainable and renewable engergy sources to run their probes and vehicles that roam around space. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters on Mars in one month and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission.

This can be hardly be called Mars exploration when only such a small area of Mars can be covered. As shown above, surely batteries are not the way to go for space exploration. How about utilizing what is abundant out there - Sunlight and Wind!

A sun-seeking rover and a probe shaped like a giant beach ball are among the newest robots being tested for their potential to explore the Martian landscape.

Basking in the Sun

A robot called Hyperion weaves through hills and around obstacles, all the while avoiding shadows as it calculates a path that maximizes its exposure to sunlight, which it relies on for power. Named for the Greek word meaning "he who follows the sun," Hyperion was designed and programmed to always point its solar panel directly at the sun.

A robot called Hyperion weaves through hills and around obstacles, all the while avoiding shadows as it calculates a path that maximizes its exposure to sunlight, which it relies on for power. Named for the Greek word meaning "he who follows the sun," Hyperion was designed and programmed to always point its solar panel directly at the sun.

"What makes Hyperion different is that it is more aware of its surroundings. We have added intelligence to this machine," said engineer Ben Shamah of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

For the past two and a half weeks, Shamah and his colleagues have been testing Hyperion in one of the bleakest and most remote places on Earth—Devon Island, north of the Arctic Circle.

Devon Island, part of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is uninhabited. Its cold, barren, and rocky terrain is the closest simulation of Martian terrain on Earth. The other advantage of the location is that it has 24 hours of sunlight—perfect for testing this solar-powered robot.

A milestone for Hyperion was completing a 24-hour, 6.1-kilometer (3.8-mile) circuit over hilly, rocky terrain and returning to its starting point with fully charged batteries. One concern had been that the robot would travel too fast or not keep its panels directed toward the sun, causing it to run out of battery power before completing its mission.

Although Hyperion must be further developed before it will be capable of exploring Mars, said Shamah, the current model has demonstrated that "sun-synchronous navigation can provide an unlimited source of energy enabling a rover to explore vast areas."

Under good conditions Hyperion plods along at about 30 centimeters (one foot) per second. This is a fairly good speed compared to previous battery dependent models. Now lets look at the other energy source that is abudant in Mars and scientists can harness it for their robots' power.

Blowing in the Wind

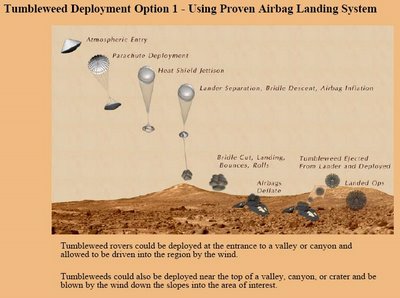

Scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have designed an explorer that can hurtle across the Martian landscape at up to 40 miles (64 kilometers) per hour.

The speedy explorer is a huge inflatable ball about six meters (19 feet) in diameter that is propelled entirely by wind power.

"Mars is very windy but the air is thin, which is why we need to use a big ball—it acts like a huge sail and catches a lot of wind," said Jack Jones of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who is leading the research.

"Mars is very windy but the air is thin, which is why we need to use a big ball—it acts like a huge sail and catches a lot of wind," said Jack Jones of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who is leading the research.

The "tumbleweed ball," as it is called, carries a payload of scientific instruments at its center, which are held in place with tension cords. Among the instruments is a radar for detecting underground water and a magnetometer for determining the location of tectonic plates. Neither task can be done from an orbiting craft.

The roving ball is also outfitted with cameras, which sit in recessed nooks on its outer surface. When the rover enters an interesting area that merits a closer look, scientists can send a signal to partially deflate the ball and stop it from rolling. When the ball has finished taking measurements, it can be reinflated to enable it to roll onward.

The idea of inflatable rovers is not new, Jones pointed out.

Beach ball-size tumbleweeds, about 0.5 meters in diameter, were tested in the past but abandoned because they frequently became wedged between rocks, making them impractical as remotely operated rovers.

The idea of using a bigger ball came when Jones and his colleagues were testing a robot with three spherical wheels in the Mojave Desert.

"One wheel just fell off and the wind caught it—carrying it up and down, and down and up, the sand dunes," said Jones. "It must have gone about a mile before we could catch up with it and stop it."

A tumbleweed ball six meters in diameter is unlikely to get stuck or wedged. It can easily roll over the mostly small rocks that litter the Martian terrain.

One concern the research team has about the tumbleweed ball rover is its lack of controllability. "I hate to admit it, but these rovers are pretty dumb," said Jones. "They just go where the wind takes them."

The research team is developing a steering mechanism, which involves shifting the payload off center to force the ball to the left or the right.

Next year, if funding permits, Jones wants to test the tumbleweeds on Devon Island. "There are not many places on Earth where we can just unleash giant tumbleweeds and let them roam around," he said.

Jones has no doubt that the tumbleweeds will dramatically increase the potential for Mars exploration. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters in one month, he noted, and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission.

Jones has no doubt that the tumbleweeds will dramatically increase the potential for Mars exploration. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters in one month, he noted, and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission.

"But tumbleweeds," he said, "could potentially cover hundreds of kilometers per day."

References:

Hyperion solar powered robot: http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=5288

Tumbleweed wind powered robot: http://centauri.larc.nasa.gov/tumbleweed

Explore Mars with Robots

There are a number of limitations and factors that are affecting exploration in distant planets and stars like Mars. One of them is battery life. NASA scientists are always looking for sustainable and renewable engergy sources to run their probes and vehicles that roam around space. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters on Mars in one month and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission.

This can be hardly be called Mars exploration when only such a small area of Mars can be covered. As shown above, surely batteries are not the way to go for space exploration. How about utilizing what is abundant out there - Sunlight and Wind!

A sun-seeking rover and a probe shaped like a giant beach ball are among the newest robots being tested for their potential to explore the Martian landscape.

Basking in the Sun

A robot called Hyperion weaves through hills and around obstacles, all the while avoiding shadows as it calculates a path that maximizes its exposure to sunlight, which it relies on for power. Named for the Greek word meaning "he who follows the sun," Hyperion was designed and programmed to always point its solar panel directly at the sun.

A robot called Hyperion weaves through hills and around obstacles, all the while avoiding shadows as it calculates a path that maximizes its exposure to sunlight, which it relies on for power. Named for the Greek word meaning "he who follows the sun," Hyperion was designed and programmed to always point its solar panel directly at the sun.

"What makes Hyperion different is that it is more aware of its surroundings. We have added intelligence to this machine," said engineer Ben Shamah of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

For the past two and a half weeks, Shamah and his colleagues have been testing Hyperion in one of the bleakest and most remote places on Earth—Devon Island, north of the Arctic Circle.

Devon Island, part of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is uninhabited. Its cold, barren, and rocky terrain is the closest simulation of Martian terrain on Earth. The other advantage of the location is that it has 24 hours of sunlight—perfect for testing this solar-powered robot.

A milestone for Hyperion was completing a 24-hour, 6.1-kilometer (3.8-mile) circuit over hilly, rocky terrain and returning to its starting point with fully charged batteries. One concern had been that the robot would travel too fast or not keep its panels directed toward the sun, causing it to run out of battery power before completing its mission.

Although Hyperion must be further developed before it will be capable of exploring Mars, said Shamah, the current model has demonstrated that "sun-synchronous navigation can provide an unlimited source of energy enabling a rover to explore vast areas."

Under good conditions Hyperion plods along at about 30 centimeters (one foot) per second. This is a fairly good speed compared to previous battery dependent models. Now lets look at the other energy source that is abudant in Mars and scientists can harness it for their robots' power.

Blowing in the Wind

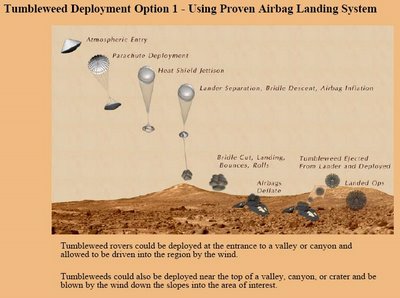

Scientists at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, have designed an explorer that can hurtle across the Martian landscape at up to 40 miles (64 kilometers) per hour.

The speedy explorer is a huge inflatable ball about six meters (19 feet) in diameter that is propelled entirely by wind power.

"Mars is very windy but the air is thin, which is why we need to use a big ball—it acts like a huge sail and catches a lot of wind," said Jack Jones of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who is leading the research.

"Mars is very windy but the air is thin, which is why we need to use a big ball—it acts like a huge sail and catches a lot of wind," said Jack Jones of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who is leading the research.The "tumbleweed ball," as it is called, carries a payload of scientific instruments at its center, which are held in place with tension cords. Among the instruments is a radar for detecting underground water and a magnetometer for determining the location of tectonic plates. Neither task can be done from an orbiting craft.

The roving ball is also outfitted with cameras, which sit in recessed nooks on its outer surface. When the rover enters an interesting area that merits a closer look, scientists can send a signal to partially deflate the ball and stop it from rolling. When the ball has finished taking measurements, it can be reinflated to enable it to roll onward.

The idea of inflatable rovers is not new, Jones pointed out.

Beach ball-size tumbleweeds, about 0.5 meters in diameter, were tested in the past but abandoned because they frequently became wedged between rocks, making them impractical as remotely operated rovers.

The idea of using a bigger ball came when Jones and his colleagues were testing a robot with three spherical wheels in the Mojave Desert.

"One wheel just fell off and the wind caught it—carrying it up and down, and down and up, the sand dunes," said Jones. "It must have gone about a mile before we could catch up with it and stop it."

A tumbleweed ball six meters in diameter is unlikely to get stuck or wedged. It can easily roll over the mostly small rocks that litter the Martian terrain.

One concern the research team has about the tumbleweed ball rover is its lack of controllability. "I hate to admit it, but these rovers are pretty dumb," said Jones. "They just go where the wind takes them."

The research team is developing a steering mechanism, which involves shifting the payload off center to force the ball to the left or the right.

Next year, if funding permits, Jones wants to test the tumbleweeds on Devon Island. "There are not many places on Earth where we can just unleash giant tumbleweeds and let them roam around," he said.

Jones has no doubt that the tumbleweeds will dramatically increase the potential for Mars exploration. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters in one month, he noted, and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission.

Jones has no doubt that the tumbleweeds will dramatically increase the potential for Mars exploration. The 1997 Sojourner rover was only able to move about 100 meters in one month, he noted, and the Mars rover planned for 2003 will travel only about one kilometer during the entire mission."But tumbleweeds," he said, "could potentially cover hundreds of kilometers per day."

References:

Hyperion solar powered robot: http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=5288

Tumbleweed wind powered robot: http://centauri.larc.nasa.gov/tumbleweed